- Home

- Brendan Cowell

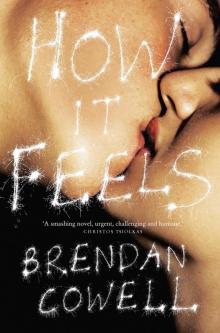

How it feels Page 3

How it feels Read online

Page 3

‘Ha ha!’ I said, and she kissed me on the mouth.

‘Did Gordon tell you what he got on his TER, bub?’ Courtney asked as we descended Grandview Parade.

‘No’, I laughed, remembering the brief phone call I’d had with my best mate earlier that day. ‘He just mumbled something like “the whole thing is shit”.’

‘What do you think he was trying to say?’

This was a familiar game only we played in private; me or Courtney would relay one of Gordon’s angry, stunted sentences then translate it to the other in grand detail. We saw it not as mockery but as a celebration of our friend’s efficient delivery. ‘I, Gordon Braithwaite, believe that the Higher School Certificate is not simply a measure of man’s intellect, but a measure of something far, far lesser than acumen – that is, “memory retention”.

I, Gordon Braithwaite, am a highly intelligent man but I have smoked way too many cones to remember fucking logarithms or what year Hitler died or whatever.’

Courtney was giggling so I ploughed on, doing Gordon’s low, British speak to perfection. ‘The Higher School Certificate is therefore a load of bullshit and I should get full marks because I can suck more bong than any fucker here and I play the drums!’

‘Sounds like he got less than fifty.’ Courtney bit her bottom lip in concern.

‘Yeah, he doesn’t want to go to university anyway – wants to make cash.’

‘He is totally right though – if that was him speaking. The HSC is a ridiculous construct, the whole thing should be wiped out and re-imagined, gearing itself towards the realities of the workplace, not some meaningless political quiz for private school kids – alienating the weak!’

I was not exactly sure about her use of ‘alienating the weak’ but I loved it when she fired up (her nostrils flaring like a boxer’s cheeks after the ninth round); these strong and driven conversations made me feel like a demigod, above the rest of the world in vibe, insight and general coolness. These were the chats of the new generation, and me and my hot girlfriend were at the fucking helm: we would take our brilliant love all the way to university and never ever apologise again!

The university adventure was sealed and locked in beyond doubt or speculation until a friend of mine from OnStage (the Year 12 state drama finals), Julien, told me about a university around three and a half hours west of Sydney in a small town south of Orange (weirdly, Orange is the home of the apple). Then he arrived at my door with his mum in a silver Tarago playing the Hair soundtrack.

The humble university grounds sat wedged between the chilly, pie-shop-littered town (every country town makes ‘the world’s best pie’) and the iconic, snaking raceway, Mount Panorama. The morning wind whipped our eyes and noses. Julien hugged me as if we had crossed the Tasman in a kayak together without a map.

‘Nelll-eeeeee! Look at us goooooo!’

Inside the theatre/media complex, tie-dyed third-year students massaged each other on crash mats, laughing and gesturing five times louder than necessary, stinking fabulously of Drum tobacco, sweet chilli sauce and carpet. Finally, after ten years of being labelled a ‘wanker’ or an ‘arty-farty wanker’ or an ‘arty-farty wanker faggot’ at school, I felt as regular as tasty cheese, shuffling down the corridor, eyes zipping over every inch of the building.

I performed Edmund from King Lear, plus my original HSC monologue Belinda (better than ever!), though I failed miserably when thrown three sand-filled balls and asked to juggle. I was moved from room to room participating in improvisations, neutral mask workshops, breathing exercises, yoga and icebreakers. The whole experience was a blur, but on the way home, as Julien’s mum pushed the Tarago past gorgeous postage-stamp towns like Oberon, Blackheath, Leura and Springbrook, I couldn’t tear my thoughts away from the open vibe and crisp, thrilling air of the campus, and ringing in my ears was the last thing Dick Hindmarsh (the bearded head of theatre) said to me as he packed up the crash mats and left the rehearsal space: ‘Don’t come here if you want to be an actor, Neil, come here if you want to create! Do you want to make something beautiful, Neil Cronk? I have a feeling you do.’

The big bulging trees that lined the wide streets, and the zestful eyes of the (stinking) students gripped my lungs – making me breathe in short, sharp pockets all the way home. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my creativity, all I knew was that I wanted to do a lot, and this place seemed to embrace that very notion. I couldn’t help but feel it was a shame not to look into it further, but I couldn’t and I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t. I’d stay quiet like I always did, like they always told me to.

Years 7 and 8 were a bit of a nightmare for me. I just couldn’t find any friends. I mean I wasn’t mad searching for them, with a sign on my head saying Please be my friend I ’m a deadset loser, but it would have been nice. I was friends with Matthew Smith from my maths class for a while. I’d go over to his house on Saturdays and listen to Faith No More and shoot baskets in the drive. But then he (overnight) became friends with David O’Brien and the next thing I knew I had an appointment on the oval after school to fight David and I had never even met the guy, really. I went to the principal and told him about the fight, hoping he would stop it, but he just peered down at me from beneath his bushy grey eyebrows and said, ‘There are certain things a man has to go through before he becomes a man.’ Which made no sense at all, because a man would not have to go through anything to become one if he was already being referred to as a man.

I unlocked my bike and rode off in the opposite direction from the oval. I knew I was in for it tomorrow, but I didn’t care: I was no fighter, especially when said duel was against someone I did not know or hold any ill feeling towards.

The next day at lunch Matthew Smith asked me to play cricket with him and his friends against the big wall. I thought, ‘Oh, this is a turnaround’, and took the tennis ball in my hand. I strode in to bowl with a relieved disposition, but I never got to roll the arm over, for David O’Brien was in the umpiring position and he slammed a cream bun in my face just as I made the delivery crease. It was a planned move, as everyone broke out in laughter. Especially Matt.

I stood up, wiped the cream off my face, walked over to David and punched him in the nose the way my father had taught me in the living room. The entire school surrounded us, everyone screaming ‘Fight! Fight! Fight!’ I wondered whether they would all be cheering ‘Dance! Dance! Dance!’ if David and I had been dancing together.

David got up and stomped towards me, at which point I recalled his position as captain of Sutherland district’s rugby union team and wished I could retract my right cross to the nose. He put a three punch on me and I fell to the ground, but I stood up, dizzily, and as he gloated to his friends I thumped him in the neck and again in the face. He fell over into the bubblers, and I swear a few guys were cheering for me now, I could hear my name through the fog of static. I’d shown some sort of masculinity and the masses were appreciative. Then David changed temperatures, holding my jaw in one hand as he delivered several blows to my mouth and eyes with the other. I woke up in the sick bay with Miss Flynn dousing me in Dettol.

Conclusion: I was better off not having friends. So I took to reclusion with fierce commitment, spending recess in the library reading about the Aztecs, and lunchtime in the music room listening to the Christian band rehearsing their dynamic set of hymns and gospels. I grew fond of such tracks as ‘Here I Am, Lord’, and often found myself humming ‘On Eagle’s Wings’ on my bike ride home. Of course Stuart was in my life, but he dropped in and out like a spider, and then took off to smash someone or root someone or something. Mum worried about me; I even overheard her talking to Dad in the kitchen, asking him if he thought I was gay or possibly even autistic. But Dad just shrugged and said, ‘I don’t know,’ and wandered off for a dump and a shower.

That winter I did think about killing myself, but to tell the truth I couldn’t choose a way. Hanging seemed really difficult, drowning just sounded so ugly with your head exploding and all, and

I hated the sight of blood so there was no way I could slit my wrists. I also found the whole suicide thing so unoriginal; it seemed everyone in Cronulla was doing it. So I plodded along in my ennui, declaring to myself that to continue on was braver than to feebly give in to the gloom and fuck up those who loved you.

Then Gordon arrived – and it was, I’m not joking, an arrival. One day I was walking through the sea of kids at school in my noble isolation, chewing on a wholegrain sandwich of Vegemite and lettuce, the next day I’m sitting with this British kid, and I’d never felt so good. Is it ok to say you fall in love with friends?

Gordon was my first true mystery and I was drawn to him accordingly. So much of my life in the Shire was known and tangible, until this spotty little British chap landed on its shores, with his restless leg and scared grey eyes. He looked so lost, scrunched up by the bins, flipping a child-sized soccer ball in his hands. Close to invisible he was, though not to me. I saw him across the yard and he saw me, two estranged boys, mislaid in the cruel circus of their age group. I walked over to him like I walked over to Courtney at her brother’s funeral, without a thought, just pure instinct, and I was right, I was so right.

I was giggly and alive around him. He was my age but I always felt so much younger. He had done stuff, and endured stuff, lived a million more lives than me. All I had done was write poems, hide from sports carnivals and play music in my room as my parents argued about clutter, whereas Gordon had lived in Wales and London and now here with me in Cronulla. Gordon had moved from town to town his whole life it seemed.

With cool abandon we threw our individual worlds to the side and built our own composite. With his broad shoulders and my broad mind we climbed into each other’s lives, hiding nothing and embracing all. When Gordon’s dad was riled and smashing up his mum, Carmen, and their house, Gordon would come to mine with his younger brother, Rocky, and stay in the rumpus room for a day or two weeks. We’d watch Bruce Lee movies and eat Vita-Weats. It made me so happy to rescue him from the hell of his house, I almost rejoiced when he called up in a tight whisper asking if he could ride over in twenty. I liked to watch him sleep, it made me feel purposeful and kind, like I imagined a shoehorn would feel, or a home electrician. Even when Gordon slept, his leg shook, he was the epitome of restlessness, so I bought him some drums and we started playing music together in his garage or mine. I wrote lyrics and spoke them low over my simple yet always slightly funky bass lines, as Gordon smashed the skins deftly and with power. Gordon was surprised how easily he took to drumming, and how good he became so quick, whereas I knew he had rhythm and the desire to use it, given the amount of hours I’d sat there watching him tap out paradiddles on his shuddering pink thighs.

‘Fuck, that’s like thirteen,’ Gordon said, counting my first clump of pubes. He already had a veritable ginger map on his area, I’d seen it heaps, wondering when my sprout would arrive. Then, one day, one fine day, I undressed and entered the shower receptacle, swapping places with my father. I began rocking from side to side, like my father had taught me, when I caught sight of my father’s face, his typically dead blue eyes glaring madly at my mid-region. I looked down, and things were never the same again.

I don’t know what effect I had had, but Gordon grew into a generally sunny bloke. He took to adventures with boundless energy, often snorting laughter out of his nose in uncontrollable bursts and for no apparent reason. He was just overwhelmed, like how a dog moans all crazy when it lands on a beach and feels all the space and water around it. Darkness fell only when we arrived on his lawn, or near his street, where the threat of what lay behind those doors seemed to crush his shoulders and he would walk towards his house like a very cold person, hunkered in and down.

Gordon’s father was Peter, and he would often answer the door with blood on his fists and a metal cup full of whisky hanging round his neck from a leather string. Since the war Peter had been haunted by all he had seen, and it manifested in him often mistaking Gordon, Rocky and Carmen for the enemy. When he wasn’t traumatised and drunk, Gordon’s dad was a beautiful singer and wonderful storyteller who could charm the pants off anyone. Gordon loved it when he was like that.

In Year 10 things changed for Gordon and me (in a big way), and I’d confidently put this wholly appreciated shift down to three contributing factors. (1) Our band The White Goods began playing assemblies and selected house parties. (2) Gordon and I had decided, in the spring of 1992, that it was time to start dressing sharp. We spent our Saturdays in the city, trawling Paddington Markets for striped t-shirts and baggy distressed Kepper jeans, and pretty soon the local cattle began to copy our fashion and in this regard we may have been considered ‘cool makers’. (3) Stuart came roaring back into my life employing Gordon and me as his official sidekicks, which pretty much ensured our protection and earnt us the sudden and confusing interest of girls.

In 1993 we turned seventeen. That was the year Gordon’s dad went missing. One morning he was in the kitchen apologising to Rocky for breaking his train set in yet another flurry of grog rage, the next he was gone, never to be seen or spoken of again. We all waited, in trepidation, for him to return, but he never did. Then one day Carmen ripped open the curtains and the sunlight poured in, we all drank champagne and orange in the kitchen, and I witnessed one of the most glorious acts of nature and liberation as Gordon laughed with all his heart; laughter from his belly expelled out his mouth in large, unshackled guffaws. Gone was the apolo getic snorting, and gone was that restless leg.

Soon after this Gordon took to marijuana with gusto. No sooner had he learnt how to suck it than he had financed a double-chamber glass bong, which he treated like the Holy Grail. No matter how ripped he got, every session concluded with Gordon cleaning the shaft with a wire brush, sanitising the cone, then folding the precious mechanism into its terry-towelling swaddling cloth. It was a ritual we came to know and love, and although he was less present and often monosyllabic and dead-looking, Gordon had found a way of accessing the ridiculousness of life and the inside-ness of music, and he honoured its access-maker. Who was I to take that away from him? I smoked pot for a bit at the start, but then I wrapped proceedings up. It freaked me out, the ultra-awareness and the stadium-sized sound of things in my brain. I already thought about things too much as it was, there was no need to enhance the experience.

Girls came in and out of our lives but the rendezvous were shortlived, for Gordon could not wait to be back in the saddle, one hand on the bong, one arm around me, laughing madly and openly as Stuart told a crazy story or made animal figures out of his cock and balls. The babble was infectious, and the meals disturbing, Stuart convincing all that entered to savour his favourite culinary concoction: English muffins with tomato paste and Vegemite. I had no idea how free we were. That’s how free I was.

4

Ron Stone loved washing his boat. Seriously, he washed it twice a week; whether he’d taken it out on the water or not he was always scrubbing away like a madman. Ron designed the garage/boatshed/ workshop with this in mind, envisaging long afternoons in the joint, washing his twenty-six-foot speedboat that he had light-heartedly named The Office. When I asked Ron why he named the boat this (and let me tell you, asking Ron a question was terrifying, the man was so tall and intimidating and he spoke so infrequently it was like that bit in Oliver where Oliver goes up and asks for more food), he told me about ‘a bloke in Cairns’ who had named his boat The Office so that whenever someone called him when he was on the boat, he could always tell the other guy (without lying), ‘I’m at The Office!’ This killed Ron, this was seriously the best thing he had ever heard, and he chortled as he told me. It was an ok joke, I guess.

Inside the Stones’ house it got way primal. Moose heads, deer heads and massive fibreglass fish lined the walls of the hall and living room, bolted in and gazing out into the open-plan space; trophies from Ron’s hunting efforts of the late eighties and early nineties. Courtney and I both agreed it was way spooky – the surrounding

family of creatures bulging out into your own home, especially with the rifle or spear gun that claimed the beasts framed and positioned on the stairwell wall. But we would never voice such opinions in this house. Even though Ron Stone was a reclusive figure, Stuart and the family hailed him Tribal Leader, and his kills were direct proof of his majesty, stealth and fierceness.

Stuart was a different kind of warrior; instead of slaying wild boar in Africa, he preferred to suck piss and shoot magpies from the balcony with his shirt off, and, funnily enough, this was exactly what he was doing when we arrived. Every time I saw Stuart with his shirt off I was reminded of how incomprehensibly long his torso was. It seemed to lift off from his rippling stomach and climb upwards for what seemed like ages before it finally met up with the faraway breast and nipple section. Girls at school were amazed that Courtney was ‘just friends’ with Stuart. It was historically implausible, for no girl had been to Stuart Stone’s house more than once without being dicked, licked or at least finger-blasted by the maniac. And even though Stu was buff as hell, tall and tanned with the chiselled Brad Pitt jaw line, Courtney preferred weedy, weird old me, and I never worried about it. I could tell she didn’t take him seriously and this comforted me. Whenever Stone did his swagger or replayed his feats in the sack she burst out laughing and he liked her for it. Courtney was probably the only chick at De La Salle College who thought he was a bit of a knob-shiner.

Bang! From the spacious deck of the waterfront house, Stuart fired his BB gun into the wall of bougainvillea that curved around the back of the house and down to the bay. A magpie fluttered and freaked out, losing a stack of its feathers, wounded, limping through the air.

‘Yeah, baby!’ Stuart said, opening his one-hundred-and-forty-mile-long arms. ‘Joseph and Mary are here! Please do take a seat in my manger for the night, oh virginal ones, and smoke cheerfully on the frankincense bong tube if you will!’

How it feels

How it feels